In the Shadow of Liberty, Stanford University Prof. Ana Raquel Minian’s history of the US government’s reliance on detention and deportation, features the emotionally and physically wrenching experiences of four immigrants: Fu Chi Hao, a Chinese student fleeing the violence of the Boxer Rebellion; Ellen Knauff, a German Jew who escaped the Holocaust, was falsely accused of being a Communist spy, and spent years in detention; Gerardo Mansour, a Cuban exile who arrived on American soil in the 1980 Mariel boatlift; and Fernando Arredondo, who left Guatemala with his wife and three daughters after his son was murdered by a gang, only to run afoul of president Donald Trump’s family separation policy.

“In America there is freedom,” Rafael told his friend Gerardo. “No one is watching you and you can say and do what you want without risking freedom for it.”

In America, “if you work, you become rich. I own two cars and a big house with all the comforts.”

And so, when President Jimmy Carter promised that the United States would welcome Cuban immigrants “with an open heart and open arms,” Gerardo pretended to be a homosexual, one of the allegedly “common criminals, lumpen, and anti-social elements” Fidel Castro permitted to leave the island, along with tens of thousands of Cuban citizens.

Minian reveals that Gerardo encountered “a deliberately pitiless” system designed to discourage future immigrants from attempting to resettle in the United States.

And he “would come to learn the costs of not being protected by the Constitution.”

All are welcome

The Supreme Court declared in 1852, “This country is open to all men who wish to come to it.”

“He who flees from crimes committed in other countries, like all others, is admitted.” And until the late 19th century, the US government passed no laws restricting immigration.

Starting in 1875, however, a series of laws barred most people from China and individuals deemed sick, likely to become public charges, or engaged in criminal or immoral activities.

Legislators, Minian writes, came to believe that “immigration restriction required immigration detention.”

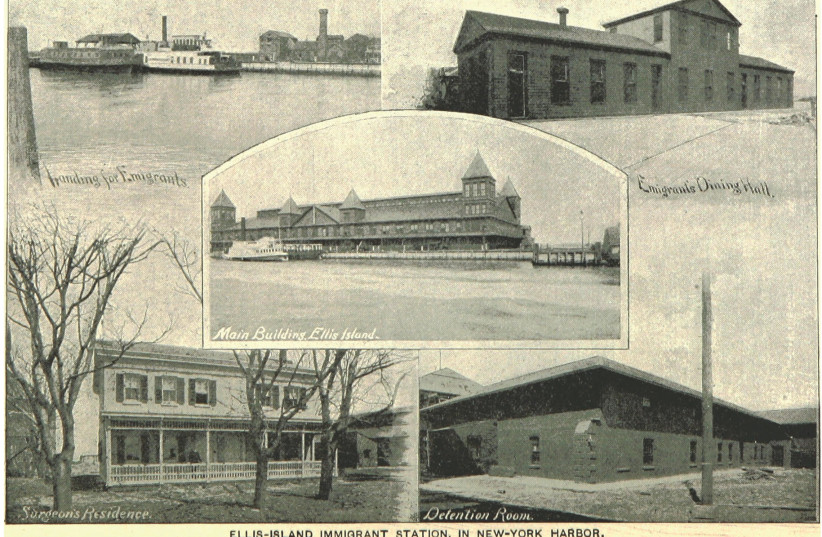

Officials initially kept immigrants on the ships that brought them to the United States but soon confined them in Christian missions, county jails, and other facilities.

In 1891, lawmakers added a provision, later known as “the entry fiction,” mandating that detention on land did not mean that the individual was actually “in” the United States and that, therefore, had rights the Constitution bestowed on “persons.” Nor did authorities permit migrants to be released on bail while their requests for admission were being considered.

Detention was expensive and often unnecessary.

In 1907, a peak year for immigration, for example, about 200,000 foreign nationals were detained. Only 6,752 of them were deported.

Litigation on behalf of Ellen Knauff, we learn, led to reforms, albeit temporary, in this system. But in the midst of the Cold War Red Scare, it would not be easy. When Ellen married her first husband, a Czech national, she lost her German citizenship. She lost her Czech citizenship when she wed Kurt Knauff, an American World War II veteran stationed in Germany in 1948. Detained on Ellis Island while authorities decided her fate, Ellen declared she was now living in “a concentration camp with steam heat and running water.” If also, she conceded, with kosher meals.

In 1949, she sought a writ of habeas corpus to contest the right of the government “to exclude from the United States, without a hearing, the alien wife” of a US citizen. In 1950, citing the entry fiction doctrine, the Supreme Court decreed Ellen could claim no right to seek admission to the country. However, Justice Robert Jackson issued a powerful dissent against this “treatment of a war bride” based on vague reasons of national security: “Security is like liberty in that many are the crimes committed in its name.”

Support for Ellen overflowed

More than 2,000 articles appeared in newspapers and magazines advocating for Ellen. With Congress poised to block expulsion, attorney-general James McGrath decided to deport her as soon as possible.

While Ellen waited at Idlewild Airport for a plane to take her back to Europe, Justice Jackson issued a stay. McGrath agreed to a hearing, but the result was the same: “There was reason to believe” she would engage in “espionage, sabotage, public disorder, or other activity subversive to national security.” In 1951, however, the Board of Immigration Appeals found her favor, and Ellen breathed “the air of free America.” Under the title “It Happened Here,” The New York Times bemoaned “how far we have strayed from the democratic process when it comes to granting foreigners permission to step upon our shores.” A blow had been struck against the entry fiction.

The writer is The Thomas and Dorothy Litwin Emeritus Professor of American Studies at Cornell University.

IN THE SHADOW OF LIBERTY:THE INVISIBLE HISTORY OF IMMIGRANT DETENTION IN THE UNITED STATESBy Ana Raquel MinianViking 384 pages; $32